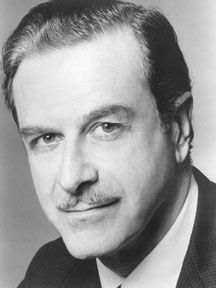

Peter Mennin

-

Sonata for Piano

Sonata for PianoStandard Binding (O4646): $24.99 Digital (O4646D): $17.49 Download (O4646D-PDF): $24.99 Piano -

String Quartet No. 2

String Quartet No. 2Standard Binding (SC11): $35.99 Digital (SC11D): $22.99 Download (SC11D-PDF): $35.99 String Quartet -

String Quartet No. 2

String Quartet No. 2Standard Binding (O4002): $39.99 Digital (O4002D): $24.99 Download (O4002D-PDF): $39.99 String Quartet -

Symphony No. 4, The Cycle

Symphony No. 4, The CycleScore and Parts (C1076): Rental Standard Binding (O3647): $35.00 Mixed Chorus

- Page Previous

- Page 1

- Page 2

- You're currently reading page 3

- Page 4

- Page Next

Born on May 17, 1923 in Erie, Pennsylvania, Peter Mennin began his formal studies at the age of seven. He was drawn to composition immediately, and by the age of eleven he was already experimenting with symphonic forms. In 1939, he entered the Oberlin Conservatory, studying composition with Normand Lockwood.

Born on May 17, 1923 in Erie, Pennsylvania, Peter Mennin began his formal studies at the age of seven. He was drawn to composition immediately, and by the age of eleven he was already experimenting with symphonic forms. In 1939, he entered the Oberlin Conservatory, studying composition with Normand Lockwood.

At eighteen, during the Second World War, he joined the U. S. Army Air Force. After his honorable discharge as a Second Lieutenant in 1943, he resumed his studies at the Eastman School of Music, receiving his Bachelor's and Master's degrees in 1945, and his Ph.D. degree in 1947.

He finished his First Symphony during the war, before he was nineteen, and heard it performed at Eastman shortly after he returned from the Service. His Second Symphony was publicly honored in New York in 1945: one movement of the work received the first Gershwin Memorial Prize, and the entire composition received the Bearns Prize in Composition from Columbia University the same year.

It was Mennin's Third Symphony, completed on his twenty-third birthday, which earned him an international reputation and solidified his position as a composer with salient gifts. The first performance in 1947 was conducted by Walter Hendl with the New York Philharmonic. Other performances in the United States and Europe followed in quick succession. Mitropoulos, Szell, Rodzinski, Reiner, and Schippers, among others, conducted this striking and original work.

In 1947, Mennin was appointed to the composition faculty of the Juilliard School in New York City, a position he retained for ten years. In 1948, he composed a Fourth Symphony, "The Cycle," for chorus and orchestra, set to his own poetry and commissioned by the Collegiate Choral. More choral music followed: Four Choruses for unaccompanied mixed chorus (1948), commissioned by the Juilliard Musical Foundation, The Christmas Story for mixed chorus, soloists, brass, timpani, and strings (1949), commissioned by the Protestant Radio Commission, and Two Choruses for SSA chorus and piano, commissioned by Sigma Alpha Iota (1949). In 1949, he also wrote Five Piano Pieces. In 1950, he composed his Fifth Symphony, commissioned by the Dallas Symphony Orchestra. The String Quartet No. 2 (1951), commissioned by the Koussevitsky Music Foundation, received the Columbia Records Chamber Music Award. The Canzona for Band was also written that year, commissioned by Edwin Franko Goldman through the League of Composers. Concertato for Orchestra ("Moby Dick") was written in 1952 on commission from the Erie Philharmonic. The Sixth Symphony, commissioned and recorded by the Louisville Orchestra, was completed in 1953. In 1955, a commission from the Juilliard Musical Foundation resulted in a Concerto for Cello, followed in 1956 by the Sonata Concertante for violin and piano, commissioned by the Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Foundation.

In 1957, Mennin spent a year in Europe on Fulbright and Guggenheim Fellowships. That year was also marked by the composition of a Piano Concerto, commissioned by the Cleveland Orchestra. When he returned to his native country in 1958, he became Director of the Peabody Conservatory of Music in Baltimore, Maryland. He held the post for four years, introducing many new ideas into the disciplines of conducting, opera production, concert structure, and administration.

In 1962, Mennin returned to the Juilliard School as its President, a position he held for twenty-one years. His tenure was the longest in Juilliard's history. He presided over an unprecedented growth for that celebrated school, guiding its move to Lincoln Center and expanding its international influence. Under his stewardship the institution established a Juilliard Theater Center, the American Opera Center, a Conductors' Training Program, a Playwrights Program, and an annual Contemporary Music Festival.

Despite this busy period in his professional life, Mennin continued to compose, producing a Sonata for Piano in 1963, commissioned by the Ford Foundation's Program for Concert Artists, a Seventh Symphony, commissioned by the Cleveland Orchestra in 1964, Cantata De Virtute for chorus, soloists, and large orchestra in 1969, commissioned by the Cincinnati Musical Festival, and Canto for Orchestra, commissioned by the Association of Women's Committees for Symphony Orchestras.

The unusual nature of Mennin's talent was recognized through many commissions and awards from foundations, networks, musical organizations, and academic institutions. He was President and chairman of the National Music Council, President of the Walter W. Naumburg Foundation, a member of the U.S. State Department Advisory Committee on the Arts, on the board of ASCAP, the American Music Center, Composer's Forum, Koussevitsky Music Foundation, and the Lincoln Center Council.

With all these responsibilities, Peter Mennin remained first and foremost a composer, and continued writing at a steady pace. The music of the last ten years of his life evinces a special interest in writing for voice, and exploring the coloristic possibilities of instrumental writing. The formal profile and energy that characterized the early works are not abandoned, but are supplemented by a new brilliance and freedom of style, which is enhanced by a greater use of the coloristic instruments of the orchestra.

The works of the seventies and eighties are Symphony No. 8, Reflections of Emily for women's chorus, piano, harp, and percussion, commissioned by the National Endowment for the Arts, and Symphony No. 9, commissioned by the National Symphony Orchestra.

The Concerto for Flute and Orchestra (again the result of a commission, this one from the New York Philharmonic), was completed four months before his death on June 17, 1983, at the age of 60. With this last work, Mennin created a rare masterpiece for the wind instrument. In many respects, the score synthesizes all the tendencies of his master years: lyricism, infused with sensuousness and brilliance, joined to intense rhythmic propulsion. It is a music of formal clarity, great vitality, and polished orchestral brilliance.

Mennin's many accomplishments as an educator and administrator will be remembered, since they are recorded in the annals of a number of our most important musical institutions. In the words of critic, editor, and composer Arthur Cohn, “Mennin’s many accomplishments as an educator and administrator will be remembered, as they are recorded in the annals of a number of our most important institutions, but it is as a composer that he will be remembered best. He left a body of work, particularly in the symphonic genre, that is basic to the American repertoire. The fact that he never associated or aligned himself with any trend or a specific school of composition allowed him to create a catalog of works that stand solidly within a self-designed tradition.”

The trademarks of the Mennin style are graphic. They appear in every composition, regardless of duration or medium of expression. Through the years, his abiding commitment to the structural possibilities of music enabled him to shed colorful light on historical forms. He brought an imaginative flexibility to traditional structures, and the evolving nature of his themes creates subtle changes within each conventional shape.

Mennin's way with motion was perhaps the cornerstone of his art. He chose to unite music and gesture. The result was that he was able to create a musical momentum in each composition arising from a unique collaboration of music and drama. The technical flash of his works is never subservient to the musical expression. As he himself wrote:"It is the total artistic statement that is of paramount importance, not the working process; it is what the music truly is, not what it is not or would like to be, that is of genuine value. With the passage of time, all that really counts is the final musical result. To the committed composer, all other matters are peripheral."